“Times, They Are a’ Changin‘” is not a strategy.

“What’s The Matter with Kids These Days” is not a plan.

I’m 37. I’ve been ordained for nearly a decade, and I’ve only ever known decline in my denomination. I started my seminary training the week of the September 11th attacks. The rapid, unpredictable change gripping the church and the world has been my constant companion from day one. It has neither surprised nor troubled me. I have taken change as a given in my vocation and have thought condescending thoughts toward those who lament or, worse, resist it.

Defending the status quo is not a vision for ministry.

But neither is embracing every change.

It’s becoming increasingly clear to me that our calling in times of changing patterns, mores, and norms is to discern which changes ought to be resisted and which ones embraced. To ask together: which changes promote bonds of community and which fray them? Which elevate virtue and which vice? Which compel compassion and which apathy?

Neither fighting for nor fighting against Change is a good unto itself, and the choice between the former and the latter is false. Today’s rebel is tomorrow’s bore.

I’ve written a bit in this space about Youth Ministry 3.0, Mark Oestreicher’s provocative vision for youth work published in 2008. Its description of the changes shaping youth culture compelled me early in my present call to cultivate a menu of student programs, each of which might appeal to different students in the church and community but none of which would have central importance.

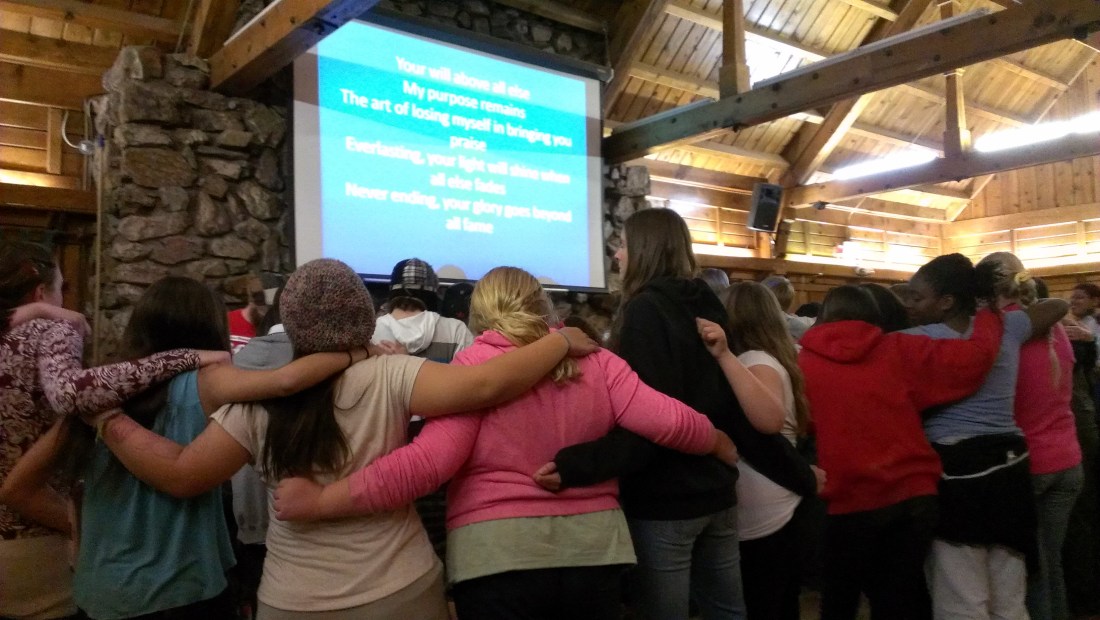

Out went The Youth Group and in came youth groups–two on Sunday afternoons and two on Wednesday afternoons. Also, special events became opportunities to engage particular groups of students in ministry and not another thing The Youth Group is expected to show up for. Scheduling a youth retreat does not cancel the weekly youth group.

Specifically, I heard clearly Oestreicher’s plea for smallness:

Smallness is both a value and a practice, though the value has to precede and continue on through the practice. Smallness values community in which teenagers can be truly known and know others, rather than being one of the crowd (even if it’s a really fun crowd). Smallness champions clusters of relationships rather than a carpet-bombing approach. Smallness waits on the still, small voice of God rather than assuming what God wants to say and broadcasting it through the best sound system money can buy. Smallness prioritizes relationships over numbers, social networks over programs, uniqueness over homogeneity, and listening to God over speaking for God (emphasis mine).

Clusters of relationships. Social networks. That’s what I’ve nurtured these past four years.

Today, though, I’m looking at these clusters and feeling acutely what they’re not doing. They’re not making much of a claim on student’s passion. They’re not holding up well to the carpet-bombing approach of homework and soccer and band and debate and water polo and A.P. classes and college applications. They’re not growing student’s knowledge of the Bible. They’re not compelling commitment to the gospel of Jesus.

Maybe they’re not experiential enough. Maybe they’re not fun enough. Maybe they’re badly led.

Or maybe the splintering changes gripping young peoples’ lives today shouldn’t be accommodated by championing smallness. Maybe these are changes to resist. Maybe bigness and uniformity gave where they appeared to be taking.

Could the last four years have been embracing changes they ought to have been resisting?